The endocrine and epigenetic impact of persistent cow milk consumption on prostate carcinogenesis

Abstract

This review analyzes the potential impact of milk-induced signal transduction on the pathogenesis of prostate cancer (PCa). Articles in PubMed until November 2021 reporting on milk intake and PCa were reviewed. Epidemiological studies identified commercial cow milk consumption as a potential risk factor of PCa. The potential impact of cow milk consumption on the pathogenesis of PCa may already begin during fetal and pubertal prostate growth, critical windows with increased vulnerability. Milk is a promotor of growth and anabolism via activating insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)/phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling. Estrogens, major steroid hormone components of commercial milk of persistently pregnant dairy cows, activate IGF-1 and mTORC1. Milk-derived signaling synergizes with common driver mutations of the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway that intersect with androgen receptor, MFG-E8, MAPK, RUNX2, MDM4, TP53, and WNT signaling, respectively. Potential exogenously induced drivers of PCa are milk-induced elevations of growth hormone, IGF-1, MFG-E8, estrogens, phytanic acid, and aflatoxins, as well as milk exosome-derived oncogenic microRNAs including miR-148a, miR-21, and miR-29b. Commercial cow milk intake, especially the consumption of pasteurized milk, which represents the closest replica of native milk, activates PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling via cow milk’s endocrine and epigenetic modes of action. Vulnerable periods for adverse nutrigenomic impacts on prostate health appear to be the fetal and pubertal growth periods, potentially priming the initiation of PCa. Cow milk-mediated overactivation of PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling synergizes with the most common genetic deviations in PCa, promoting PCa initiation, progression, and early recurrence.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the sixth leading cause of cancer death among men worldwide and is expected to reach 2.3 million new cases and 740,000 deaths by 2040[1]. The highest incidence rates are observed in Australia, New Zealand, North America, Western and Northern Europe, and the Caribbean. The lowest rates are found in South-Central Asia, Northern Africa, and Southeast and Eastern Asia[2,3]. According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2020 (GLOBOCAN), PCa contributes to 7.3% of all cancers[3]. The median age of PCa diagnosis is 68 years, while 10% of new cases in the USA are diagnosed in men aged ≤ 55 years[4]. Western diet and lifestyle have been linked to PCa prevalence[5-10]. Substantial lifestyle changes took place in Japan after World War 2, where a 20-fold increase in milk intake was associated with a 25-fold increased death rate of PCa[11].

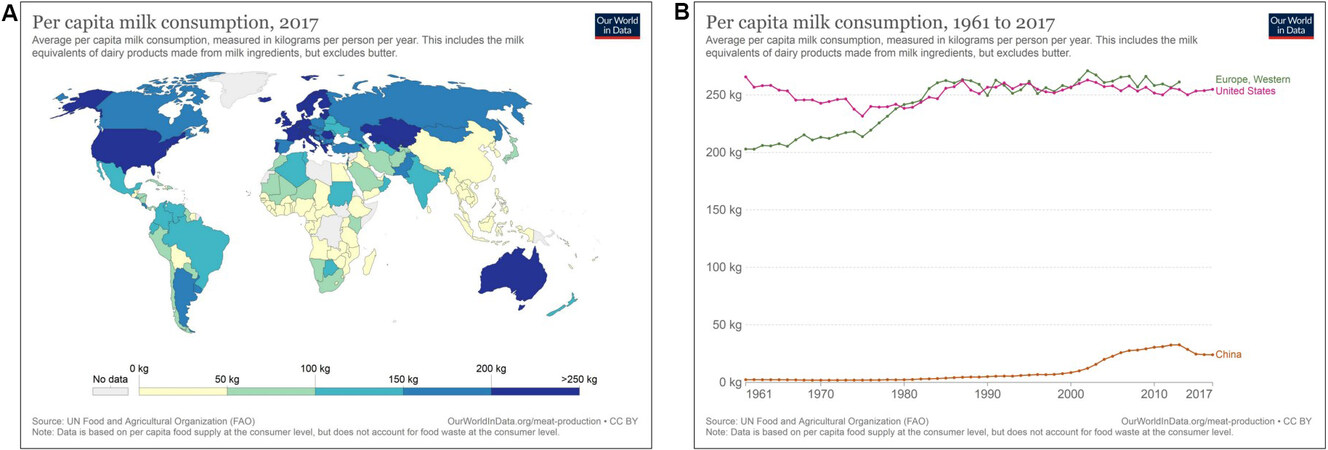

Accumulated evidence confirms that cow milk consumption is positively related to the risk of PCa[12-14]. Milk and dairy products are substantial components of nutrition in Western industrialized countries as compared to Asian or North African countries [Figure 1][15]. In 2019, the per capita cow milk consumption in Germany was 49.5 L[16]. Higher milk consumption is reported in Scandinavian countries. In Sweden, the annual per capita milk consumption declined from 2007 to 2018 from 130.5 to 98.2 L[17]. The annual per capita milk consumption in the USA declined from 89.4 kg in 2000 to 64.0 kg in 2019[18]. In Asian populations, milk consumption is much lower. In 2019, Chinese people consumed on average only 12.5 kg of milk and dairy products per year[19].

Figure 1. (A) Per capita consumption (kg) of milk and milk-derived products worldwide in 2017. (B) Comparison of per capita consumption (kg) of milk and milk-derived products during 1961-2017 in Western Europe, the United States, and China according to Our World in Data[15].

It is the intention of this review to relate milk-derived signaling pathways with the molecular pathology of PCa. To understand milk’s impact on the pathogenesis of PCa, it is of key importance to appreciate milk’s biological nature as an endocrine and epigenetic system generated by the lactation genome to promote mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-driven postnatal growth, translation, and anabolism[20], a critical mode of cell signaling maintained by the consumption of commercial dairy milk[21]. Evidence is presented that the nutrigenomic signaling of milk converges with common oncogenic aberrations of PCa cells.

GENETIC DEVIATIONS ACTIVATING PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 IN PCa

Oncogenic activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT (protein kinase B)-mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway is a frequent finding in PCa that promotes tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and resistance to therapy[22,23]. PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling is elevated in a high proportion of PCa and castration-resistant PCa (CRPC)[24-27]. Reduced expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), a critical tumor suppressor of PCa, correlates with PCa progression and poor prognosis[28]. In fact, PTEN is one of the most frequently deleted genes in PCa[29-34]. Notably, PTEN loss in primary PCa specimens correlates with high Gleason score and advanced disease[35]. Aberrant gene expression of PI3K pathway components is common in PCa and occurs in 42% and 100% of primary and metastatic PCa specimens, respectively[36-40]. It is of crucial importance that the PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 cascade interacts with androgen receptor (AR), RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and Wingless (WNT) signaling pathways[22]. Of note, AKT-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear extrusion of FoxO1, a nuclear suppressor of AR[41-45], activates androgen signaling[43,44]. Notably, AR regulates L-type amino acid transporters (LATs) that are of pivotal importance for the cellular uptake of mTORC1-activating branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), especially leucine[46]. In comparison to other protein sources, whey proteins exhibit the highest amounts of leucine[47,48]. LAT1 and LAT3 mediate the uptake of leucine and other essential amino acids. PCa cells express LAT1 and LAT3 to maintain sufficient levels of leucine required for mTORC1-dependent cancer cell growth[46,49]. LAT inhibition decreased PCa cell growth and mTORC1 activity. AR-mediated LAT3 expression maintained levels of amino acid influx through ATF4 regulation of LAT1 expression after amino acid deprivation[46]. High levels of LAT3 are observed in primary disease, whereas increased levels of LAT1 are detected in PCa metastasis after hormone ablation[46]. Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-activated PI3K/AKT signaling also stimulates cellular leucine import through LAT3 in PCa cell lines[50]. LAT inhibition could thus be an effective therapeutic strategy against PCa[51,52].

Furthermore, overactivation of PI3K-AKT signaling attenuates the inhibitory effect of FoxO1 on RUNT-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) transcriptional activity, promoting PCa cell migration and invasion[53]. Increased RUNX2 activation has been related to metastatic disease[54], especially tumor progression in the bone[55,56].

The frequency of common genetic deviations of genes in the PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 pathway in PCa is presented in Table 1 according to the works of Shorning et al.[22] and Armenia et al.[39].

Frequency of common genetic alterations in the PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 pathway in PCa

| Altered genes | Frequency in PCa (%) |

| PTEN deletion/mutation | 16.4-32.0 |

| DEPTOR amplification | 5.1-21.4 |

| SGK mutation/amplification | 5.6-20.5 (SGK3) 0.2-2.7 (SGK1) |

| FOXO deletion | 0-15.2 (FOXO1) 4.5-13.4 (FOXO3) |

| MAP3K7 deletion | 5.9-14.8 |

| RRAGD deletion | 6.5-14.4 |

| SESN1 mutation/deletion | 5.4-13.6 |

| PIK3CA mutation/amplification | 5.5-11.5 |

| PIK3C2B mutation/amplification | 1.4-11.5 |

| PDPK1 amplification | 0-8.1 |

Overactivated mTORC1 signaling plays a crucial role in PCa initiation and progression[57-62].

Taken together, substantial evidence underlines the importance of genetic deviations in PCa cells and PCa cancer stem cells enhancing PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling.

Epigenetic upregulation of PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 in PCa

Not only genetic but also epigenetic deviations contribute to PCa tumorigenesis and disease progression. Epigenetic alterations change DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the pattern of microRNA (miR) expression[63-68].

MicroRNA-21 in PCa

miR-21 is regarded as a critical oncomiR contributing to PCa carcinogenesis and progression[69,70]. miR-21 targets the mRNAs of key tumor suppressor genes including PTEN[71], programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4)[72], and forkhead box O1A[73,74]. Of note, FoxO3a, which is deregulated in PCa[75], inhibits the expression of miR-21[76]. In contrast, androgens enhance the expression of miR-21, and AR-regulated miR-21 promotes hormone-dependent and -independent PCa growth[77]. miR-21 and miR-375 of urinary exosomes have recently been reported to serve as biomarkers for the detection and prognosis of PCa[78,79]. In accordance, urine miR-21-5p is regarded as a potential non-invasive biomarker in patients with PCa[80,81]. Thus, upregulated miR-21 and miR-30c in serum/plasma emerged as biomarkers of PCa[82], as well as increased expression of miR-21 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells[83]. Furthermore, miR-21 is significantly upregulated in PCa compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia[84,85]. The expression of miR-21 and WNT-11 are associated with high Gleason scores in PCa tissues, promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in aggressive PCa cells[86]. Further target genes of miR-21 are presented in Table 2.

Target genes of miR-21 related to the pathogenesis and progression of PCa

| miR-21 targets | Regulatory proteins | Ref. |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | [71] |

| PDCD4 | Programmed cell death 4 | [72] |

| FOXO1A | Forkhead box transcription factor O1a | [73,74] |

| KLF5 | Kruppel-like factor 5 | [87] |

| IGFBP3 | IGF binding protein 3 | [88] |

| CDKN1C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C | [89] |

| MARCKS | Myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate | [90] |

| TGFBR2 | Transforming growth factor β-receptor II | [91] |

| FBXO11 | F-box only protein 11 | [92] |

| RECK | Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with KAZAL motifs | [93] |

Thus, there is compelling evidence that miR-21 including circulating miR-21, which is elevated in the serum and exosomes of PCa patients, plays an important role in PCa carcinogenesis, progression, and metastasis[75-95].

MicroRNA-148a in PCa

miR-148a is another oncogenic miR that plays a pivotal role in PCa[96-99]. Increased levels of miR-148a-3p in serum are associated with PCa[96]. miR-148a-3p expression is increased in PCa tissue and exhibits higher expression levels correlating with increased Gleason score[97]. miR-148a is an AR-responsive miR promoting LNCaP prostate cell growth by repressing its target cullin-associated neddylation-dissociated protein 1[99]. A significant growth advantage for LNCaP cells transfected with pre-miR-148a was found with significantly increased numbers of cells in the S phase[100]. miR-148a silences cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B. miR-148a transfection into LNCaP cells increased S-phase transition and enhanced cell proliferation[101]. Further target genes of miR-148a are B-cell translocation gene 2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-interacting protein 1 (PIK3IP1)[100]. PIK3IP1 directly binds to the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3K and downregulates PI3K activity[102]. PIK3IP1 negatively regulates PI3K activity and thereby suppresses activation of AKT[102]. miR-148a-mediated suppression of PIK3IP1 thus enhances PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling. It has recently been demonstrated that the E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1)/DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) inhibitory axis of AR transcription is activated during the emergence of CRPC[103]. It has been shown that miR-148a-mediated suppression of DNMT1 induces the expression of apoptotic genes in hormone-refractory PCa cells[104]. In contrast, Lee et al.[105] provided evidence that reduced expression of DNMT1 was associated with EMT induction and cancer stem cell phenotype, enhancing tumorigenesis and metastasis of PCa. In a synergistic fashion with miR-21, miR-148a suppresses the expression of PTEN and DNMT1[98,106-110]. miR-21- and miR-148a-mediated suppression of DNMT1 with consecutive promoter gene demethylation increases the expression of insulin (INS)[111], IGF-1 (IGF1)[112,113], and mechanistic target of rapamycin (TOR)[114]. These are developmental genes of the insulin/IGF-1/PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling cascade, which is upregulated in PCa. Collectively, there is compelling evidence that both miR-21 and miR-148a modify epigenetic regulation of PCa, enhancing PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signal transduction.

MILK-INDUCED PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 SIGNALING

Calcium

Earlier studies suspected dairy calcium as a promoter of PCa pathogenesis[115]. The milk calcium content differs between cattle breeds, exhibiting the lowest calcium content in Holstein-Friesian (1275.0 ±

Calcium-independent milk-induced mTORC1 activation

Current research interest focuses on the pathogenic role of milk-induced elevations of IGF-1 in PCa[125]. In fact, overwhelming evidence accumulated over two decades supports the view that increased circulating levels of IGF-1 as well as local IGF-1/IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) signaling promote PCa initiation and progression[126-151]. The perception of milk has changed from a “pure food source” to an “endocrine and epigenetically active biologic system”, promoting IGF-1-PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling substantially augmented by milk’s exosomal miRs[20,152,153]. Milk signaling functionally synergizes with dominant oncogenic driver mutations of PCa including androgen signaling, disturbed DNA repair, and mutations enhancing PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling[21,154].

Despite recent progress in milk’s molecular biology and its sophisticated physiological functions[20,152,153], nutrition science and dairy industry-supported reviews present a positive view on milk as a nutrient for metabolic health, providing valuable proteins, macronutrients, oligosaccharides, calcium, vitamins, and other micronutrients[155-159]. None of those studies in the field of nutrition and epidemiological research appreciates milk’s biological role as an mTORC1-driving system of mammalian evolution physiologically restricted to the postnatal growth period[20,152,153,160]. In fact, there is growing evidence in various disciplines of medicine that milk consumption is associated with adverse health effects, increasing overall mortality[161-165]. Milk consumption has been related to several common mTORC1-driven cancers of Western civilization, especially PCa[166-175], breast cancer[176-183], hepatocellular carcinoma[184-187], and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[188]. Notably, overactivated mTORC1 signaling is a common hallmark of PCa[21,22,27,57-61], breast cancer[189-194], hepatocellular carcinoma[195-200], and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[201-204]. Based on a recent review of the literature, Vasconcelos et al.[154] confirmed a possible relationship between milk consumption and mTORC1-mediated initiation and progression of PCa.

Oncogenic activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 pathway is a frequent aberration in PCa pathogenesis[22,23]. There is an intimate crosstalk between the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 cascade and multiple other signaling pathways that promote PCa progression[22,23]. Specifically, PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling cooperates with AR, MAPK, and WNT signaling cascades[22,23]. To elucidate milk’s impact on mTORC1-dependent translation[20] and PCa initiation and progression[21], deeper insights into milk’s signaling pathways are mandatory.

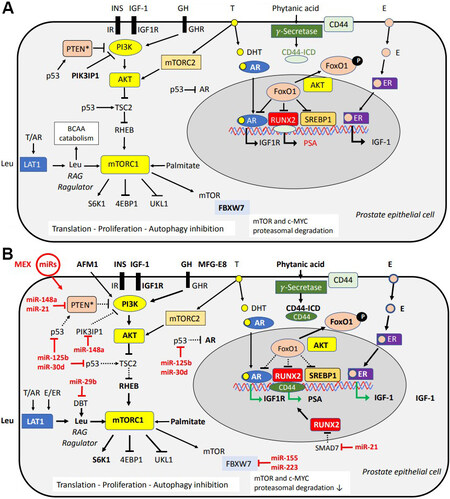

mTORC1 is the cell’s central hub for the regulation of nutrient- and growth factor-dependent cell growth and anabolism[205-211]. To fulfill its biological function as promotor of postnatal growth, milk activates five major pathways stimulating mTORC1 via: (1) growth factors including growth hormone (GH), insulin, and IGF-1; (2) amino acids, especially BCAAs; (3) milk fat-derived palmitic acid; (4) the milk sugar lactose β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-D-glucose; and (5) epigenetic modifiers, especially milk exosome (MEX)-derived miRs. Activated PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling in PCa is presented in Figure 2A. Figure 2B illustrates superimposed milk and milk miR signaling over-activating the PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling cascade in PCa cells.

Figure 2. (A) Synopsis of PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling pathways activated in prostate cancer (PCa) cells. (B) Superimposed nutrigenomic effects of milk signaling. Milk-induced and milk-derived hormones (insulin, GH, IGF-1, MFG-E8, and estrogens) activate PI3K and AKT, which in turn activate mTORC1.

Milk-derived essential amino acids (prototype leucine) activate mTORC1, increasing cell proliferation. MEX-derived miRs augment mTORC1 signaling and modify transcriptional activity in PCa. miR-148a and miR-21 suppress PTEN, which is commonly mutated or deleted in PCa. Increased AKT activity results in nuclear translocation of FoxO1, a key nuclear suppressor of AR, RUNX2, and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1. Milk-derived estrogens (E) may induce further transcription of IGF-1. RUNX2 is upregulated in PCa and controls the transcription of prostate specific antigen (PSA) and promotes bone metastasis. Phytanic acid activates γ-secretase, which cleaves CD44 releasing CD44 intracellular domain (CD44-ICD) that functions as a nuclear transcription factor cooperating with RUNX2. MEX-derived

Growth hormone

Milk consumption enhances GH levels in children and peak GH levels in adults[212,213]. Already two decades ago, the GH-IGF-1 axis was implicated in prostate carcinogenesis[214]. PCa cells express both GH and GH receptor (GHR)[215-217]. As shown in LNCaP cells, GH induces time- and dose-dependent signaling events. These include phosphorylation of Janus kinase 2, GHR, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, p42/p44 MAPK and AKT, respectively. Furthermore, GH modifies AR expression[215]. In androgen-dependent LNCaP cells, estradiol (E2), cortisol, and IGF-1 and IGF-2 all stimulate GH binding[216]. Human GH promotes IGF and β-E2 receptor (ERβ) gene expressions and interacts with IGF-1 and E2 to stimulate androgen-dependent LNCaP cell proliferation[217]. Furthermore, exogenous and autocrine GH augments the migration and invasion of LNCaP cells, dependent upon PI3K, STAT5, and MEK1/2 pathways[218].

In contrast, patients with Laron syndrome, who present dwarfism due to a genetic loss-of-function mutation of GHR[219,220], exhibit failures in the GH-GHR-IGF-1 signal transduction process, resulting in congenital IGF-1 deficiency associated with a reduced incidence of cancers including PCa[221-224]. Notably, disruption of GH signaling retards early stages of prostate carcinogenesis in the C3(1)/T antigen mouse and Probasin/TAg rat model[225,226]. GH-releasing hormone receptor antagonists decreased cell viability and provoked a reduction in proliferation in LNCaP and PC3 cells[227]. Recent evidence indicates that GH induction following androgen deprivation therapy or AR inhibition may contribute to the CRPC progression by bypassing androgen growth requirements[228]. In fact, GH induces expression of the AR splice variant 7, which correlates with antiandrogen resistance and induces IGF-1 that is implicated in PCa progression and ligand-independent AR activation[228]. Increased GH signaling via milk consumption may thus promote PCa development and CRPC progression.

Insulin-like growth factor 1

Milk consumption increases circulating IGF-1 levels in children, adolescents, and adults[212,213,229-235]. Whereas a cross-sectional study in Bavaria of 526 men and women aged 18-80 years showed that only milk but not yogurt and cheese intake increased serum IGF-1 levels[234], a larger British cohort study including 11,815 participants reported that milk and yogurt protein, but not cheese protein, increased serum IGF-1 concentrations[235]. Hoppe et al.[236] observed an increase in serum insulin by isolated consumption of whey protein and an increase of IGF-1 by isolated casein supplementation after seven days in prepubertal boys.

IGF-1 is a component of human and bovine milk[237-239]. Bovine IGF-1 exhibits an identical amino acid sequence compared to human IGF-1[240]. The GH-IGF-1 axis is of physiological importance for infant growth[241,242]. Of note, it is not the oral uptake of bovine GH and IGF-1 in dairy milk that increases serum IGF-1 levels, but the induction of hepatic IGF-1 synthesis and release after milk consumption[212,239]. Tryptophan, a major amino acid enriched in milk proteins, is the precursor of serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)], which via 5-HT2 receptors stimulates hypothalamic GHRH release and pituitary GH secretion, thus increasing serum GH levels[243]. Hepatic GH/GHR signaling is the major stimulus increasing circulatory IGF-1 levels [Figure 2][244,245].

The milk protein-derived amino acids tryptophan, methionine, and arginine synergistically enhance hepatic IGF-1 synthesis and secretion[212,246-252]. Exposure to bovine MEX to cultured human colonic LS174T cells enhanced the expression of glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP94)[253], the most abundant intraluminal endoplasmic reticulum chaperone that aids in the synthesis of IGF-1, IGF-2, and proinsulin[254,255].

IGF-1 activates the PI3K-AKT pathway. Activated AKT phosphorylates tuberin (TSC2), which promotes the dissociation of TSC2 from the lysosomal membrane activating RAS homolog enriched in brain (RHEB). RHEB finally activates mTORC1 at the lysosomal membrane[207,210,256-260]. IGF-1 is a pivotal promoter of linear growth and body size[261-265].

Milk protein-derived insulinotropic BCAAs are released by intestinal hydrolysis. They induce postprandial hyperinsulinemia explaining milk’s high insulinemic index compared to its low glycemic index[266,267]. Fast intestinal hydrolysis of whey protein-derived amino acids contributes to milk’s high insulinemic effect[236,268-271]. In a synergistic fashion, insulin and IGF-1 activate PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling and thereby promote growth and anabolism of target tissues[257,259,272-276].

Amino acids

Compared to other protein sources, milk protein and casein contain high amounts leucine and methionine. Compared to meat, whey proteins are highly enriched in leucine[47,277]. In addition, milk protein exhibits a high glutamine content (8.1 g/100 g protein) compared to beef (glutamine 4.75 g/100 g protein)[278]. Glutamine via the glutaminolysis pathway also results in mTORC1 activation[279,280]. Major milk-derived amino acids such as leucine, arginine, and methionine are sensed via sestrin 2, cellular arginine sensor for mTORC1, and S-adenosylmethionine sensor upstream of mTOR, respectively. These amino acids stimulate mTORC1 activation through RAG GTPase pathways[281-298]. Glutamine activates mTORC1 through a RAG GTPase-independent mechanism that requires ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1)[297]. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase (LRS) is another amino acid-dependent regulator of mTORC1[299,300]. LRS senses intracellular leucine concentration and directly binds to RAG GTPase, the mediator of amino acid signaling to mTORC1, in an amino acid-dependent manner and functions as a GTPase-activating protein for RAG GTPase to activate mTORC1[300]. Moreover, LRS operates as a leucine sensor for the activation of the class III PI3K Vps34 that mediates amino acid signaling to mTORC1 by regulating lysosomal translocation and activation of the phospholipase PLD1[301]. mTORC1 activation involves leucine sensing, LRS translocation to the lysosome, and interaction with RAGD[302-305]. There is a further function of LRS1 in glucose-dependent control of leucine usage[306]. Upon glucose starvation, LRS1 is phosphorylated by Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1 at the residues crucial for leucine binding. Phosphorylated LRS1 decreases leucine binding, which may inhibit protein synthesis thereby saving energy[306].

In addition, arginine relieves allosteric inhibition of RHEB by TSC[307]. Arginine cooperates with growth factor signaling, which further dissociates TSC2 from lysosomes and activates of mTORC1[307].

Taken together, full mTORC1 activation only occurs when both RAG and RHEB GTPase pathways are fully activated, neither being sufficient alone[295]. The final activators of growth factor and amino acids signaling pathways, RHEB and RAGs, converge at the lysosome to activate mTORC1 [Figure 2][281-296,308].

Palmitic acid

The predominant saturated fatty acid of milk triacylglycerols (TAGs) is palmitic acid (C16:0), which is transported in milk fat globules (MFGs)[309,310]; MFGs, in turn, transfer energy through their TAG core[311]. After intestinal TAG hydrolysis and re-esterification into chylomicrons, palmitic acid serves as an energy source and fuels mitochondrial β-oxidation for ATP synthesis[312,313]. ATP inhibits AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and thereby activates mTORC1[314-316]. As shown in skeletal muscle cells, palmitate activates mTORC1/p70S6K signaling by Raptor phosphorylation[317], stimulates mTORC1 activation at the lysosome[318,319], and induces lipid deposition in HepG2 cells via activation of the mTORC1/S6 kinase 1 (S6K1)/SREBP-1c pathway[320].

It has been shown by dynamic microfluidic Raman technology that palmitic acid and arachidonic acid exhibit a high uptake in PC3 cells, whereas docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid have inhibitory effects on the uptake of palmitic acid and arachidonic acid[321]. The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study Group reported relative PCa risks [95% confidence intervals (CI)] on comparison of the highest with the lowest quartiles of myristic acid and palmitic acid of 1.62 (1.15-2.29) and 1.53 (1.07-2.20), respectively[322]. A recently published study in the United States including 49,472 men with an average follow-up period of 11.2 years and a median total dairy intake of 101 g/1000 kcal showed that regular fat dairy product intake was associated with late-stage PCa risk (HR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.04-1.82 comparing the highest with lowest quartile) and 2% fat milk intake with advanced PCa risk (HR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.02-1.28 comparing higher than median intake with no intake group)[323].

Milk fat globule-EGF factor 8

MFG membrane proteins, predominantly MFG epidermal growth factor 8 (MFG-E8, also known as lactadherin), stimulates cell proliferation through the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway[324-327]. Increased levels of MFG-E8 found in tissue and plasma exosomes from PCa patients have been compared with controls[327,328]. Notably, M2 polarization of PCa-associated macrophages is induced by MFG-E8-mediated efferocytosis[327]. Of note, MFG-E8 is a major constituent of MFG membranes[329], but it is detectable only in minor amounts in milk EVs and exosomes[326-328]. However, MFG-E8 mRNA has been detected in bovine MEX[329-332]. Remarkably, MFG-E8 promotes the absorption of dietary TAGs and the cellular uptake of fatty acids and is linked to obesity[333]. MFG-E8 coordinates fatty acid uptake through αvβ3 integrin- and αvβ5 integrin-dependent phosphorylation of AKT by PI3K and mTOR complex 2, leading to translocation of CD36 antigen and fatty acid transport protein 1 from cytoplasmic vesicles to the cell surface[333]. Thus, MFG-E8 plays a key role in the absorption and storage of dietary fats[333]. Recent evidence indicates that insulin receptor signaling is autoregulated through MFG-E8 and the αvβ5 integrin[334]. Intriguingly, αvβ5 expression is upregulated in PCa and PCa cells[335,336], and the differentiation of PCa seems to influence integrin expression and subcellular distribution[335]. Notably, αvβ5 integrin expression is increased in plasma and urine EVs derived from PCa patients[337]. Whole milk, especially milk fat with enriched amounts of MFG-E8, may additionally promote PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling in PCa [Figure 2].

Phytanic acid

The lipid fraction of milk contains phytanic acid (3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-hexadecanoic acid) representing 0.7% of milk total long-chain fatty acids[338]. Depending on the intensity of grass feeding, the content of phytanic acid varies from 9.7 mg/100 g in whole milk to 200 mg/100 g total milk lipids and represents a marker of organic milk production[339-341]. Higher phytanic acid intake, although unrelated to the risk of localized PCa, was associated with increased risks of advanced PCa[342]. It has been demonstrated in rat aortic smooth muscle cells that phytanic acid reduces the expression of IGF-1 receptor but increases γ-secretase activity[343]. Notably, γ-secretase mediates the intramembranous cleavage of CD44[344], a major adhesion molecule for the extracellular matrix components that is implicated in a wide variety of physiological and pathological processes including the regulation of EMT, cancer growth, and metastasis[345-351]. CD44 intracellular domain (CD44-ICD) acts as a signal transduction molecule translocating into the nucleus[352]. A strong functional relationship between CD44-ICD and RUNX2 has recently been shown in AR-positive PC3 cells[353]. In the nucleus, CD44-ICD and RUNX2 interact, and this interaction was higher in PC3 cells transfected with RUNX2 cDNA. In contrast, inhibition of CD44 cleavage with a γ-secretase inhibitor reduced the formation of CD44-ICD. Overexpression of RUNX2 augmented the expression of metastasis-related genes (e.g., MMP-9 and osteopontin), which resulted in increased migration and tumorsphere formation[353]. There is compelling evidence that RUNX2 enhances cell growth and responses to androgen and TGFβ in PCa cells[354]. Remarkably, RUNX2 stimulates AR responsive expression of the PSA[354]. Both RUNX1 and RUNX2 cooperate with prostate-derived ETS factor to activate the transcription of PSA upstream regulatory region[355]. Recently, a cooperation between AR and RUNX2 in the stimulation of oncogenes such as invasion-promoting SNAIL family transcription factor SNAI2 has been demonstrated[356]. RUNX2 not only is a master organizer of gene transcription in developing and maturing osteoblasts[357], which is related to the physiological function of milk increasing linear and skeletal growth[261,262], but it also promotes PCa bone metastasis[54,55,358]. It is thus of critical concern that cow milk-derived phytanic acid may induce γ-secretase-mediated CD44-ICD-RUNX2 nuclear signaling[56]. Of importance, Baier et al.[359] demonstrated that the expression of RUNX2 increased by 31% in blood mononuclear cells 6 h after commercial cow milk consumption in adult healthy volunteers compared to baseline.

Plasma phytanic acid concentrations have been significantly associated with intake of dairy fat[360]. Higher phytanic acid intake, although unrelated to the risk of localized PCa, was associated with increased risks of advanced PCa predominantly by phytanic acid obtained from dairy products[342], whereas no overall association has been detected between serum phytanic and pristanic acid levels and PCa risk[342,361]. In contrast, Xu et al.[362] reported that serum levels of phytanic acid among PCa patients were significantly higher than those of unaffected controls, suggestive of an association between phytanic acid and PCa risk [Figure 2].

Increasing evidence links PCa risk with polymorphisms in the α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR) gene and branched-chain fatty acids derived from specific sources of dietary fats[363-366]. AMACR is a catalyst in peroxisomal β-oxidation of branched-chain fatty acids found in milk and dairy products[367]. AMACR expression is actually downregulated in hormone-refractory metastatic tissue relative to the primary tumor[368]. An association between low AMACR expression at diagnosis and an increased risk of biochemical recurrence and fatal PCa has been reported[369]. Furthermore, lower AMACR intensity was associated with higher PSA levels and more advanced clinical stage at diagnosis, and there was a non-significant trend for higher risk of lethal outcomes[370]. In contrast, other studies report AMACR overexpression as an early event in prostate tumorigenesis that may precede morphologic evidence of malignant transformation[371,372].

Estrogens

Dairy cows continuously lactate throughout almost their entire pregnancy, explaining increased amounts of estrogens and progesterone in commercial milk[373]. A significant increase in serum estrone (E1) and progesterone levels has been shown in men and children who consumed 600 mL/m2 of cow milk. In addition, urine levels of E1, estradiol (E2), estriol (E3), and pregnanediol significantly increased in all consumers, allowing the conclusion that milk-derived estrogens were absorbed[373]. Milk of Swiss Holstein cows exhibited average hormone levels of E1 = 159 ng/kg, 17β-E2 = 6 ng/kg, 17α-E2 = 31 ng/kg, 4-androstenedione = 684 ng/kg, progesterone = 15,486 ng/kg, 17-hydroxyprogesterone = 214 ng/kg, cortisol = 235 ng/kg, and cortisone = 112 ng/kg, whereas E3 was below the limit of detection[374]. According to Malekinejad et al.[375], the major cow milk estrogens were free and deconjugated E1 (6.2-1266 ng/L), α-E2 (7.2-322 ng/L), and β-E2 (5.6-51 ng/L), whereas E3 was below the detection limit. The calculated daily estrogen intake through milk consumption was 372 ng[375]. In commercial milk samples, Tso et al.[376] confirmed that E1 (23-67 ng/L) was the major free estrogen, whereas E2 and E3 concentrations were below the limit of detection. Several conjugated estrogen metabolites were identified: 17β-E2-3-glucuronide (71-289 ng/L), E1-3-sulfate (60-240 ng/L), 17β-E2-3,17β-sulfate (< LOD to 30 ng/L), and E3-glucuronide (< LOD of 25 ng/L)[376]. Thus, endogenous and exogenous steroids derived from dairy products produced from whole milk are a source of exogenous steroid exposure to humans[377].

Obesity has been proposed to be involved in the pathogenesis and more aggressive courses of PCa[378,379]. Notably, a twofold elevation of serum E1 and 17β-E2 levels was observed in a group of morbidly obese men[380]. Thus, obese men with increased endogenous estrogen production may represent a vulnerable group, especially during further exogenous estrogen exposure derived from milk and dairy products. There is recent concern that estrogens represent an under-recognized contributor in PCa development and progression[381,382]. Of notice, AR and ERα expression changes during PCa progression, both independently and co-expressed[383]. In high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia specimens (epithelium and stroma), an increase in the population of double-positive (AR+/ERα+) cells has been observed, whereas double-negative (AR-/ERα-) cells significantly decreased in advanced PCa, from 65% in benign prostate tissue to 30% in metastasis tissue[383].

There is extensive crosstalk among estrogens, androgens, and IGF-1 signaling in PCa cells. In LNCaP and PC3 cells, E1 increased the level of AR and IGF-1 expression[384,385]. The upregulation of ERα and estrogen-regulated progesterone receptor (PR) during PCa progression and hormone-refractory PCa suggests that estrogens and progestins stimulate tumor growth[386]. A potentially aggressive molecular subtype of PCa exhibiting TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion is regulated by ER. TMPRSS2-ERG expression increased by ERα agonist but decreased by ERβ agonists[386]. Thus, increasing evidence demonstrates that local estrogens contribute to prostate carcinogenesis and tumor progression[387]. It has also been reported in breast and renal carcinoma cells that estrogens and IGF-1 have synergistic effects on tumor cell growth[388-391]. In fact, IGF1R expression in PCa is upregulated by both androgens and estrogens sensitizing PCa cells to the mitogenic effects of IGF-1[392]. Of note, mTORC1 has been identified as a critical checkpoint for estrogen signaling[393]. The downstream effector of mTORC1, the ribosomal S6K1, activates ERα via phosphorylation of S167. ERα binding to Raptor promotes its translocation into the nucleus upon estrogen stimulation. In addition, phosphorylation of ERα on S104/106 by mTOR kinase activates transcription of ER target genes[394]. The molecular crosstalk between mTORC1 and ERα in the pathogenesis of PCa may be augmented by milk-mediated estrogens and milk-induced IGF-1, which synergistically activate mTORC1. Treatment of LNCaP cells with androgen or E2 triggers simultaneous association of AR and ERβ with SRC oncogene, activates the SRC/RAF-1/ERK-2 pathway, and stimulates cell proliferation[394]. It has been demonstrated in cortical neurons that ER protein interaction with p85, the regulatory unit of PI3K, leads to activation of AKT and ERK1/2[395]. PCa stem cells lack AR explaining the resistance to androgen deprivation therapy[396]. However, PCa stem cells express classical (α and/or β) and novel (GPR30) ERs[396]. Gene expression profiles of CD133+ 4/CD44+ PCa stem cells showed that many ribosomal proteins and translation initiation factors that constitute the mTOR complex were highly expressed[62].

Galactose

The lactose content of milk makes up around 2%-8% by weight. Lactose hydrolysis provides glucose and galactose, which both activate mTORC1. The great majority of men in Western societies consuming milk and dairy products is lactose-tolerant and can hydrolyze the disaccharide lactose into glucose and galactose. The total galactose content of bovine milk is 2.4 g/100 g[397]. Increased sugar consumption from sweetened beverages was associated with increased risk of PCa for men in the highest quartile of sugar consumption (HR = 1.21, 95%CI: 1.06-1.39), and there was a linear trend (P < 0.01)[398]. In adults, hepatic galactose elimination capacity is related to body weight and decreases slowly with age[399,400]. Notably, galactose increases oxidative stress, which has recently been linked to increased all-cause mortality by consumption of non-fermented milk[162-165]. Galactose is a mitochondrial stressor experimentally used for the induction of aging and neurodegeneration[401-404]. Disturbed oxidant/antioxidant balance has been implicated in the pathophysiology of PCa, especially in high-risk PCa subjects[405]. The ginsenoside Rg1 decreases oxidative stress and downregulates AKT/mTORC1 signaling and attenuates cognitive impairment in mice and senescence of neural stem cells induced by galactose[406]. Accumulated evidence underlines that oxidative stress is of critical importance in prostate carcinogenesis[407-414]. There is a close interaction between AMPK and AKT on the ROS homeostasis via mTOR and FOXO regulation, which is of key importance for cancer cells[415].

In a galactose-induced pseudo-aging mouse model, miR-21 significantly increased, whereas miR-21 knockout mice were resistant to galactose-induced alterations in aging-markers[416]. Of note, treatment of rat spinal cord neurons with hydrogen peroxide, a galactose-induced ROS, upregulates miR-21 expression[417].

Milk exosomal microRNAs

Pasteurized commercial cow milk transfers bioavailable extracellular vesicles (EVs) including MEX and their gene-regulatory miRs[418-423]. There is recent evidence that vigorous heat‐treatment such as ultraheat-treatment (UHT: 135 °C, > 1 s) and boiling (100 °C) of commercial cow milk destroys MEVs and MEX and their miR cargo, including miR‐148a[421,424], whereas pasteurization (72-78 °C, > 15 s) of commercial milk did not affect total MEV numbers and preserved nearly 25%-40% of milk’s total small RNAs, including miR‐148a[424]. Bacterial fermentation of milk also attacks MEX and reduces their miR content, as demonstrated for miR-21 and miR-29b in yogurt cultures[425]. Translational evidence indicates that pasteurized non-fermented cow milk is a stronger promoter of mTORC1 activity compared to fermented milk products[426]. Bovine and human MEX and their miRs resist degradative conditions in the gastrointestinal tract, reach the systemic circulation, and distribute in various tissues[420,427-434]. In fact, increasing evidence presented by studies in humans and animal models supports the view that MEX and their miRs are bioavailable, reach the systemic circulation[420,422,434-437], and modify gene expression of the milk recipient[359,418,437-439]. It has been demonstrated that bovine MEX increased the expression of GRP94[253], which is a key endoplasmic reticulum chaperone enhancing the synthesis of insulin, IGF-1, and

MicroRNA-21

Bovine miR-21 is an abundant signature miR of cow milk[451]. Bovine and human miR-21 exhibit nucleotide sequence homology[452-454]. Plasma concentrations of Bos taurus (bta)-miR-21-5p was > 100% higher 6 h after commercial cow milk consumption of healthy human volunteers than before milk consumption, strengthening the bioavailability of milk-derived miRs in human milk consumers[422]. Sadri et al.[437] showed that, after oral gavage of fluorophore-labeled bovine MEX to pregnant mice, miR-21-5p and miR-30d accumulated in placenta and embryos. Experimental evidence provided in murine models demonstrates that oral uptake of bovine MEX results in MEX distribution in various tissues and organs[420,437,455]. MEX miR-21 most likely also affects the prostate gland, where it may target IGFBP3, PTEN, FoxO1, FoxO3, PDCD4, etc., enhancing IGF-1-PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling.

Marquez et al.[456] established post-transcriptional regulation of SMAD7 by miR-21. miR-21 is a key negative regulator of SMAD7 and directly interacts with the 3’UTR of SMAD7 mRNA[456,457]. Importantly,

MicroRNA-148a

miR-148a represents the most abundant miR in cow milk, milk fat, EVs, and MEX[418,436,451,464-467]. miR-148a is highly conserved among mammals[418,468] and has been identified as a domestication gene of dairy cows, enhancing milk yield[469,470]. Human and bovine milk miR-148a nucleotide sequences are identical[418,468,471,472]. Milk-derived bovine miR-148a is thus able to affect gene expression of human milk consumers (cross-species communication)[473]. DNMT1 is a major target of miR-148a[109,110], which explains MEX-mediated suppression of DNMT1 expression[418,438], a pivotal postnatal mechanism modifying epigenetic regulation activating mTORC1 signaling[153,439,443,474]. In fact, DNMT1 inhibition upregulates the expression of the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)[475], which promotes the expression of mTOR (MTOR)[476]. By targeting the catalytic subunit α1 of AMPK (PRKAA1) as well as the AMPK regulatory subunit γ2 (PRKAG2), miR-148a attenuates the expression AMPK[477,478]. AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 and Raptor suppresses mTORC1 activity[315,479]. Importantly, miR-148a inhibits PTEN, the upstream negative regulator of PI3K[106-108], which is downregulated in PCa[22,39]. In addition, miR-148a targets PIK3IP1, the direct negative regulator of PI3K[102]. Thus, milk miR-148a epigenetically augments several checkpoints activating mTORC1 [Figure 2B].

MicroRNA-155 and microRNA-223

miR-155 and miR-223 are dominant immune regulatory miRs of bovine milk[427,428,466,480,481]. miR-155 targets IGFBP3[482]. In synergy with miR-148a, miR-155 also suppresses the expression of PTEN[483]. Both miR-155 and miR-223 suppress the proteasomal degradation mTOR via targeting F-box and WD40 domain protein 7 (FBXW7)[484,485], a critical regulatory checkpoint involved in ubiquitination-dependent degradation of mTOR[486]. Moreover, FBXW7-mediated mTOR degradation cooperates with PTEN in tumor suppression[486]. In addition, FBXW7 promotes the degradation of cyclin E, c-MYC, MCL-1, JUN, NOTCH, and aurora kinase A (AURKA)[487]. In primary PCa, decreased expression of FBXW7 mRNA compared to normal prostate tissues has been detected[488]. Significant overexpression and gene amplification of AURKA and n-MYC have been detected in 40% of neuroendocrine PCa and 5% of PCa, respectively[489].

MicroRNA-125b and microRNA-30d

miR-125b, another abundant miR component of cow milk, resists gastrointestinal digestion[428,465,481]. miR-30d belongs to the top 10 expressed milk miRs when comparing the sequence data of various species including Bos taurus and Homo sapiens[418,436,490,491]. After oral gavage of bovine MEX transfected with fluorophore (IRDye)-labeled miR-30d as well as miR-21 to C57BL/6 mice, these miRs accumulated in murine placenta and embryos[437]. Of note, miR-125b and miR-30d are key inhibitors of TP53, the guardian of the genome[492-494]. In fact, increased expression of miR-125b enhances PCa growth[495] and attenuates the expression of p14(ARF), modifying p53-dependent and -independent apoptosis in PCa[496]. Loss of p53 function plays a critical role in prostate carcinogenesis, especially in early stage[497]. Bovine MEX miR-125b and miR-30d via targeting TP53 may represent another mechanistic link of milk signaling, enhancing mTORC1 in PCa[498]. Notably, p53 induces the expression of a group of p53 target genes in the IGF-1/AKT/mTORC1 pathway. These gene products are negative regulators of the IGF-1/AKT/mTORC1 pathway in response to stress signals[498]. They are IGFBP3[499], PTEN[500-503], TSC2[500], and AMPK β1[500]. Furthermore, p53 is a key inhibitor of AR expression[504]. Milk miR-125b- and miR-30d-mediated suppression of p53 thus attenuates the activity of crucial negative regulators of androgen and mTORC1 signaling, both related to PCa pathogenesis [Figure 2B][494,498].

Xie et al.[448] demonstrated that porcine MEX miRs reduced the expression of p53 in intestinal epithelial cells. The expression of p53 is primarily controlled by the interaction of mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) and MDM4, which are both negative regulators of p53 expression[505]. MDM4 suppresses p53 transcriptional activity and facilitates p53 proteasomal degradation via binding MDM2’s E3 ligase activity towards p53[505]. Overexpression of MDM4 has recently been detected in PCa tissue and increases with disease progression[506-508]. Recent transcriptomic characterization of MEX isolated from cow, donkey, and goat milk identified MDM4 as a central node protein for all three species, indicating a conserved checkpoint with higher numbers of interconnections[509]. Notably, MEX-mediated attenuation p53 signaling has been implicated to play a role in the pathogenesis of PCa and acne vulgaris[494].

Taken together, an interactive network of milk miRs (miR-21, miR-30d, miR-125b, miR148a, and miR-155) provides an epigenetic regulatory layer that inactivates p53 and activates PI3K-AKT-mTORC1-signaling, which drives PCa carcinogenesis[510]. Of note, miR-30d is a critical osteomiR, promoting RUNX2 expression[511], which is closely linked to RUNX2-mediated bone metastasis in PCa[54,56].

MicroRNA-29b

miR-29b, another prominent miR of commercial cow milk, survives pasteurization and storage[419]. As shown in intestinal epithelial cells, bovine MEX miR-29b is taken up by endocytosis[512]. In a dose-dependent manner, plasma levels of miR-29b increased 6 h after consumption of 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 L of commercial milk and affected blood monocyte gene expression[359]. In a synergistic fashion with miR-148a- and miR-21-mediated inhibition of DNMT1, miR-29b attenuates DNA methylation via suppression of DNMT3A/B[513-516]. Thus, milk-derived miRs via attenuation of DNA methylation of developmental genes such as INS and IGF1 enhance their expression, resulting in increased mTORC1 activity[443].

miR-29b suppresses the catabolism of BCAAs via targeting the mRNA for the dihydrolipoamide branched-chain transacylase (DBT). DBT is the E1α-core subunit of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKD), which degrades BCAAs[517]. The activity of BCKD is regulated by BCKD kinase, which phosphorylates two serine residues in the E1α subunit and thereby inhibits BCKD. Insulin is a known stimulator of BCKD kinase expression, thereby inhibiting BCKD, which results in increased cellular levels of BCAAs[518-523]. In synergy with insulin, MEX miR-29b inhibits the oxidative catabolism of BCAAs required for mTORC1 activation at both the PI3K-AKT-TSC2-RHEB and the BCAA-RAG-Ragulator-RHEB pathway. Intriguingly, increased expression of PCa EV-associated miR-29b-3p could be detected in PCa patients compared to controls[524].

Of importance, it has been shown in osteoblasts that miR-29b induces protein and mRNA expression of RUNX2[525]. Baier et al.[359] demonstrated increased expression of RUNX2 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy volunteers 6 h after consumption of commercial cow milk. Thus, milk-induced PI3K-AKT signaling with AKT-mediated nuclear extrusion of FoxO1[53] as well as MEX miR-29b-induced RUNX2 expression and enhanced RUNX2 activity[525] provide potential mechanisms for the promotion of PCa bone metastasis[54-56,358].

Milk consumption via upregulation of RUNX2[359] may not only stimulate skeletal development[459,526,527] and linear growth in childhood[261-264] but also promote bone metastasis of PCa [Figure 2B][528].

Bovine milk and meat factors

Small circular single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) sequences have been detected in commercial milk[529-533]. These replication-competent bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF1 and BMMF2) are a specific class of infectious agents spanning between bacterial plasmid and circular ssDNA viruses with similarities to the genomic structure of hepatitis deltavirus[534]. BMMF Rep protein has been found in close vicinity of CD68+ macrophages in the interstitial lamina propria adjacent to colorectal cancer tissues[535]. BMMF1 DNA was isolated from the same tissue regions. Compared to cancer-free controls, Rep and CD68+ exhibited increased expression in peritumor cancer tissues[535]. At present, no experimental data on BMMFs in PCa tissue are available[536].

Aflatoxins

Ruminants metabolize aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) ingested by contaminated food to aflatoxin M1 (AFM1). AFM1 is the hydroxylated mycotoxin that is excreted into milk[537-540]. The increase of AFM1 concentrations in milk of maize-fed cows due to the climate change is a matter of concern[541]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer classified AFB1 and AFM1 as human carcinogens of group 1[542,543]. AFM1 is relatively stable during pasteurization, storage, and processing[544-546]. Scaglioni et al.[547] analyzed AFB1 and AFM1 concentrations of pasteurized and UHT milk and found levels for both aflatoxins in the range of 0.7-

Smith et al.[548] demonstrated a rapid uptake of AFB1 by the rat and dog prostate. Notably, the expression of androgen-inducible aldehyde reductase, a member of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily, exhibits 80% amino acid sequence homology with rat aflatoxin B1 aldehyde reductase and is associated with growth-related processes in regrowing rat prostate after androgen replacement[549]. Aflatoxin B1 aldehyde reductases, specifically the NADPH-dependent aldo-keto reductases of rat (AKR7A1) and human (AKR7A2), are known to metabolize the AFB1 dihydrodiol by forming AFB1 dialcohol[550,551]. Milk-derived aflatoxins may thus modify aldo-keto reductase activities, which are in the focus of recent PCa research[552-554]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated in lung cancer cell lines that AFB1 upregulates insulin receptor substrate 2; induces SRC, AKT, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation; and stimulates cancer cell migration, which was inhibited by saracatinib[555], a kinase inhibitor under investigation in the treatment of PCa[556-559]. Thus, milk-derived aflatoxins may amplify SRC- and AKT-mediated prostate carcinogenesis. Table 3 summarizes all milk-derived signals that increase PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling.

Overactivated PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling in PCa compared to milk signaling

| Factor | Prostate cancer | Ref. | Milk-derived signaling | Ref. |

| GH | GH and GHR is expressed in PCa tissue; activates PCa cell proliferation and PI3K; induces hepatic IGF-1 secretion; induces AR splice variant 7 | [215-218,228] | Milk consumption increases GH serum levels in children and adults | [212,213] |

| IGF-1 | Systemically and locally increased in PCa | [125-151] | Milk-induced IGF-1 increases serum levels in all age groups, component of bovine milk; activates PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling | [212-213,229-235,237-239] |

| MFG-E8 | Higher expression in PCa and serum exosomes of PCa patients; interacts with αvβ5 integrin | [327,328] | Component of MFG membranes; MFG-E8 mRNA is a cargo of MEX; promotes PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling | [324-327,329,332] |

| Estrogens | ERα is expressed in PCa and promotes PCa progression; increases expression of AR and IGF-1 by E1 in PCa cells | [381-385] | Increased levels of milk estrogens of permanently pregnant dairy cows, especially elevation of E1 | [373] |

| miR-148a | OncomiR of PCa, correlates with Gleason score; targets the PI3K inhibitor PIK3IP1 increasing PI3K activity; inhibits PTEN and DNMT1 expression | [97-100,106-110] | Most abundant miR of bovine milk and MEX surviving pasteurization; identical with human miR-148a; targets DNMT1; enhances expression of INS, IGF1, and TOR and suppresses AMPK activity | [418,421,436,451,454,478,464-467] |

| miR-21 | Biomarker and oncomiR of PCa progession; inhibits PTEN, FOXO1, and SMAD7 expression; increases RUNX2 expression | [69,70,78-95,456-458] | Signature miR of cow milk and MEX; increases in serum after milk consumption; identical with human miR-21; bovine MEX miR-21 accumulates in peripheral murine tissues | [420,422,438,451] |

| miR-125b | Enhances PCa growth, suppresses p53, the inhibitor of AR and mTORC1 | [492-495] | Dominant and resistant miR of commercial milk | [428,465,481] |

| miR-30d | OncomiR of PCa promoting RUNX2 expression; suppresses p53, the negative regulator of AR and mTORC1 | [494,498,510,511] | Belongs to the top 10 miRs of bovine milk; component of bovine MEX accumulating in distant murine tissues afer oral gavage | [418,436,437,490,491] |

| miR-155 | Reduced expression of FBXW7 in PCa | [487,488] | miR component of cow milk; targets PTEN and FBXW7 and thereby activates mTORC1 signaling | [483,484,486] |

| miR-223 | Reduced expression of FBXW7 in PCa | [487,488] | miR component of cow milk; targets FBXW7 and attenuates proteasomal mTOR and oncogen degradation | [485,486] |

| miR-29b | Marker of EVs of PCa | [524] | Dose-dependent increase in serum 6 h after milk consumption; attenuates BCAA catabolism via targeting DBT; induces RUNX2 expression | [359,517,525] |

| BCAA | PCa cells are leucine addicts and increase intracellular leucine content via AR-mediated upregulation of LATs for mTORC1-driven growth | [46,49] | Compared to other protein sources, whey and casein proteins contain high amounts of leucine as well as glutamine, critical amino acids activating mTORC1 | [277-298] |

| Palmitic acid | PCa cells exhibit high uptake of palmitic acid; palmitic acid intake correlates with PCa risk | [321,322] | Palmitic acid is the most abundant saturated fatty acid of milk triacylglycerols; palmitic acid activates mTORC1 at the lysosome; MFG-E8 promotes fatty acid uptake and deposition | [311,318,319,333] |

| Aflatoxin (M, B1) | Rapid uptake of AFB1 in rat and dog prostate | [548] | Commercial milk is contaminated with aflatoxins; AFM1 levels rise in maize-fed cows | [537-541,548] |

| mTORC1 | Upregulated in PCa; involved in PCa intiation and progression; phosphorylation of ERα activating ER target gene expression | [57-62,393] | Milk via insulin/IGF-1 signaling and milk-derived BCAAs (leucine) activates mTORC1 further augmented by milk-derived miRs, especially miR-148a and miR-21 | [20,21,154] |

| FoxO1 | Inactivated by increased PI3K-AKT signaling, functions as nuclear cosuppressor of AR | [41-44,53] | Nuclear FoxO1 inactivation by milk consumption via AKT-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear extrusion | [609,611] |

| Phytanic acid | Associated with PCa risk; increases γ-secretase activity, which cleaves CD44 that interacts with RUNX2 | [339-342,353,362] | Branched-chain fatty acid of milk, increased by organic milk production | [339-342] |

| RUNX2 | Increased RUNX2 expression; bone metastasis, increases PSA transcription; is suppressed by nuclear FoxO1 | [53,55,56,352] | Increased 31% in blood mononuclear cells 6 h after milk consumption | [359] |

| DNMT1 | Reduced expression associated with EMT and cancer stem cell phenotype | [105] | Bovine MEX miR-148a suppresses DNMT1 expression | [418,438,443] |

| Calcium | Thought to be involved in PCa pathogenesis (early studies) | [115-119,124] | Major mineral of milk; questionable influence of dairy calcium on the prostate as circulatory calcium levels are maintained within close limits | [116] |

MILK’S IMPACT ON DEVELOPMENTAL PERIODS OF PCa

Fetal prostate growth

Prostate organogenesis includes organ specification, epithelial budding, branching morphogenesis, canalization, and cytodifferentiation[560]. Activated AR‐positive murine epithelium initiates budding at E17.5. Ductal expansion and branching continues during postnatal development, leading to formation of a fully functional prostate by puberty[561-563].

IGF-1 plays a key role in fetal prostate development[561]. Prostate glands from 44-day-old IGF-1-deficient mice were smaller than those from wild-type mice and exhibited fewer terminal duct tips and branch points and deficits in tertiary and quaternary branching, indicating a specific impairment in gland structure[564]. Furthermore, IGF-1 controls prostate fibromuscular development of the prostatic gland, whereas IGF-1 inhibition prevented both fibromuscular and glandular development in eugonadal mice[565]. Castration rapidly decreased local IGF-1 levels and inhibited its effects in the ventral prostate in mice, whereas local injection of IGF-1 increased vascular density and epithelial cell proliferation in intact mice but had no effect in castrated animals[566]. Studies using mice with liver-specific IGF-1 knockout have demonstrated that liver-derived IGF-1, constituting a major part of circulating IGF-1, is an important endocrine factor involved in a variety of physiological and pathological processes[567]. Notably, locally derived IGF-1 cannot replace liver-derived IGF-1 for the regulation of a large number of other parameters including GH secretion, cortical bone mass, and prostate size[567].

IGF-1 is a regulator of intrauterine growth, and circulating concentrations are reduced in intrauterine growth-restricted fetuses[568]. During fetal life, IGF-1 is mostly secreted by the placenta[569]. Positive correlations among birthweight (BW), gestational age, and umbilical cord serum IGF-1 levels have been reported[569,570]. Thus, increased BW may represent systemic fetal exposure to IGF-1, which may affect prostate branching morphogenesis that may be over-stimulated by maternal milk intake raising maternal systemic IGF-1 levels[231-236].

Downstream PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling plays a crucial role for prostatic morphogenesis[571]. PI3K/mTORC1 signaling is necessary for prostatic epithelial bud invasion of surrounding mesenchyme. The balance of PI3K and downstream mTORC1/C2 activity as a critical regulator of prostatic epithelial morphogenesis[571].

RUNX2 plays an important role in branching morphogenesis of the prostate[572]. IGF-1-PI3K-AKT-mediated nuclear extrusion of FoxO1 enhances nuclear RUNX2 activity[53]. miR-21, which is transferred via MEX, accumulates in the placenta and fetal tissues[420,437] and may further augment RUNX2-dependent prostate morphogenesis and stem cell activation[572]. RUNX2 was detected during early prostate development (E16.5). In adult mice, RUNX2 was expressed in basal and luminal cells of ventral and anterior lobes. Prostate-selective deletion of RUNX2 severely inhibited growth and maturation of tubules in the anterior prostate and reduced expression of stem cell markers and prostate-associated genes[572]. Milk-induced changes of growth trajectories during pregnancy and fetal development via IGF-1 and miR-21 signaling may thus disturb early prostate morphogenesis, increasing subsequent PCa risk in adult life. Increased cow milk intake during the first trimester of pregnancy has recently been positively associated with general and abdominal visceral fat mass and lean mass at the age of 10 years[573].

BW and PCa risk

BW, an indicator of fetal growth, is related to placental weight[574] and has been identified as a risk factor of PCa[575-578]. Compared with twins with a BW of 2500-2999 g, the hazard ratio (95%CI) for twins with a higher BW (≥ 3000 g) corresponded to 1.22 (0.94-1.57). In analyses within twin pairs, in which both twins had a BW of ≥ 2500 g, a 500 g increase in BW was associated with an increased risk of PCa within dizygotic twin pairs [odds ratio (OR) = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.02-1.57)], but not within monozygotic twin pairs (OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 0.61-1.84)[578]. Especially, BW ≥ 4250 g was associated with significantly higher PCa incidence [62% (CI: 4%-151%)] and PCa mortality [82% (CI: 3%-221%)] than BW 3001-4249 g[576]. High BW is related to increased risks of total and aggressive/lethal PCa[577], underlining that intrauterine exposures may enhance PCa risk and course. In fact, the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study reported a protective effect of lower BW on risk of total and aggressive PCa[579].

Remarkably, maternal milk consumption but not the intake of fermented milk products (cheese) was associated with fetal weight gain and higher BW[580,581], as subsequently confirmed by systematic reviews[582-584]. In contrast to fermented milk with degraded MEX[425], raw and pasteurized milk delivers MEX and MEX miR-21[418,422,424,451], which in murine models reach the placenta and peripheral tissues[420,437] and have been related with placental weight and fetal overgrowths (macrosomia)[585,586]. Milk protein-derived essential amino acids and MEX-derived miRs, especially miR-21 and miR-148a, promote mTORC1 activity. Increased trophoblast mTORC1 activity determines placental-fetal transfer of amino acids and glucose and thus fetal growth and BW[587-591]. Of note, mTORC1 signaling regulates the expression of trophoblast genes involved in ribosome and protein synthesis, mitochondrial function, lipid metabolism, nutrient transport, and angiogenesis, representing novel links between mTORC1 signaling and multiple placental functions critical for fetal growth and development[592]. It is worth mentioning that other nutritional factors unrelated to milk intake, such as total animal protein intake during pregnancy as well as other nutritional factors such as ω-3 fatty acid intake and folic acid supplementation, have an influence on BW, which are not discussed in this review. Taken together, epidemiological and translational evidence supports the view that maternal milk consumption during pregnancy modifies fetal mTORC1-driven growth trajectories that determine BW and may also affect early prostate development and morphogenesis.

Height during puberty and PCa risk

According to the Copenhagen School Health Records Register and the Danish Cancer Registry, childhood height at age 13 years showed a positive association with PCa-specific mortality[593-596]. The PCa-promoting effect of height at 13 years was not entirely dependent on adult height, suggesting different modes of action[596]. These findings implicate late childhood and adolescence are critical exposure windows of interest that underlie the association between height and PCa[593]. According to the Longitudinal Studies of Child Health and Development, fat and animal protein intake during childhood was positively related with height at age 13 and adult height[597]. Notably, an earlier age at peak height velocity was associated with a diet high in fat and animal protein and low in vegetable protein during childhood[597]. Childhood diet and accelerated growth thus influence earlier pubertal timing and taller attained height in males, supporting their contribution in the pathogenesis of PCa[597].

Notably, The NHANES 1999-2002 study reported that consumption of milk, in contrast to other dairy products, is related to height among US preschool children[598]. The frequency of milk consumption and milk intake were identified as significant predictors of height at 12-18 years[599]. Almon et al.[600], who explored the potential relationship among the LCT (lactase) C>T-13910 polymorphism, milk consumption, and height in a sample of Swedish preadolescents and adolescents, reported a positive association between milk consumption and height in preadolescents and adolescents. In fact, increased consumption of cow milk, which leads to higher levels of IGF-1 in circulation, promotes increased velocity of linear growth[261,264].

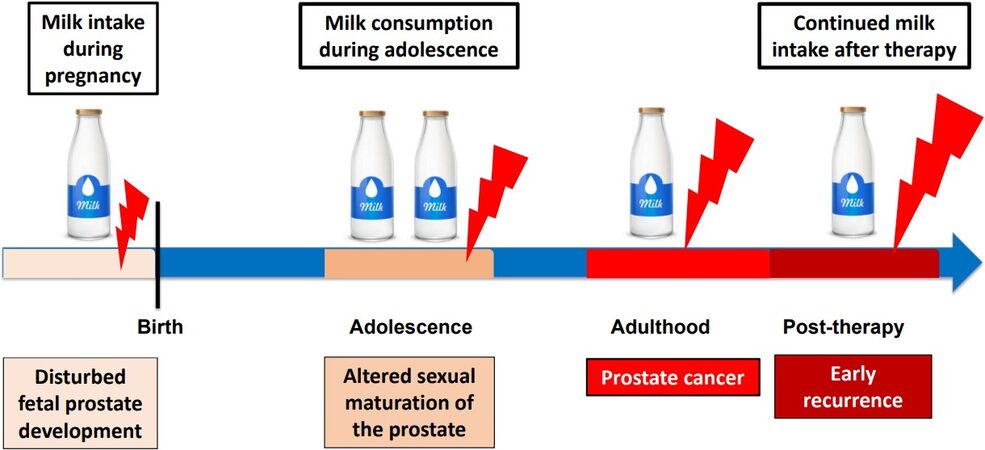

In a population-based cohort of 8894 men born between 1907 and 1935, Torfadottir et al.[168] studied the effects of early-life residency in Iceland and differences in milk intake in relation to the risk of PCa later in life. Remarkably, a 3.2-fold risk of advanced PCa was related to daily milk consumption in adolescence (vs. less than daily), but not consumption in midlife or currently. Accordingly, frequent milk intake especially in adolescence increases risk of advanced PCa[168]. Lan et al.[10] recently analyzed dietary data of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study from 162,816 participants over a follow-up period of 14 years to investigate potential associations for milk, cheese, ice cream, total dairy, and calcium intake at ages 12-13 years with incident total (n = 17,729), advanced (n = 2348), and fatal PCa (n = 827). Their findings also support the contribution of milk intake during adolescence for increased risk of PCa [Figure 3][10].

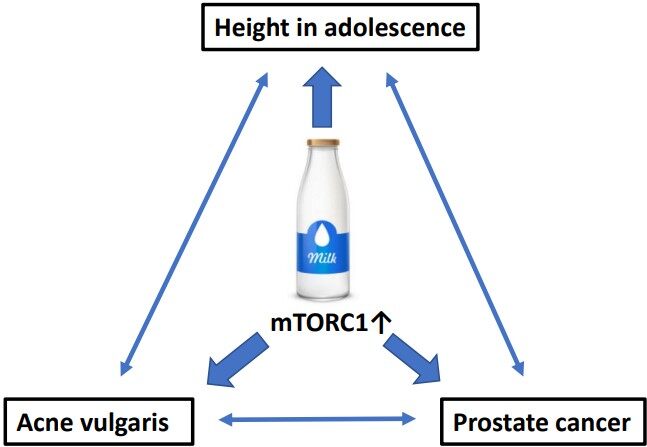

Remarkably, milk consumption during adolescence has also been associated with acne vulgaris, the most common inflammatory skin disease of adolescents in Western civilizations[601-607]. Notably, acne risk is related with height at puberty[608]. A cross-sectional population-based study on 6200 boys showed that 12-15-year-old boys with acne were taller and heavier than those without acne[608]. In analogy to PCa, both androgens and IGF-1 induce the sebaceous gland disease acne vulgaris, which is associated with increased glandular mTORC1 activity[609-611]. It is thus not surprising that an epidemiological association between height and acne during adolescence and PCa during adult life has been observed [Figure 4][612-614].

DISPUTABLE STUDIES FOR MILK-PCa RISK EVALUATION

Cell cultures

There are several examples of investigations that apply questionable study designs to analyze the relationship between milk consumption and PCa risk. Tate et al.[615] added cow milk to LNCaP cells and observed an increased growth rate of over 30%. However, under physiological conditions, a prostate cell will never be exposed to whole milk. Transferable factors of milk, such as BCAAs, IGF-1, estrogens, aflatoxins, exosomal MFG-E8, and exosomal miRs, may eventually reach the prostate and may accumulate during persistent milk consumption.

Park et al.[616] exposed PCa cells (LNCaP and PC3) and immortalized normal prostate cells (RWPE1) with either 0.1 or 1 mg/mL of α-casein and total casein extracted from bovine milk. Whereas α-casein and total casein did not affect the proliferations of RWPE1 cells, PC3 and LNCaP cells showed a significant but IGF-1-independent increase in cell proliferation.

It is known that LNCaP and PC-3 cells take up leucine in a PI3K-AKT-dependent manner[50]. Casein hydrolysis may provide abundant leucine for PCa proliferation. Notably, total and α-casein contain high amounts of leucine of 9.2 and 7.9 g/100g protein, respectively[617]. Kim et al.[618] studied gene expression profiles of PC3 cells after exposure to α-casein and showed activated PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling. Under in vivo conditions, however, α-casein will never reach the prostate and PCa tissue, whereas α-casein-derived BCAAs after intestinal hydrolysis and uptake into the blood circulation may affect PCa via BCAA-mTORC1 signaling.

Animal experiments

Bernichtein et al.[619] performed an interventional animal study using two mouse models of fully penetrant genetically induced prostate tumorigenesis that were investigated at the stages of benign hyperplasia (probasin-Prl mice, Pb-Prl) or pre-cancerous prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesions (KIMAP mice). They reported that mice were fed high milk diets (skim or whole milk) for 15-27 weeks depending on the kinetics of prostate tumor development in each model. They reported that that high milk consumption did not promote progression of existing prostate tumors when assessed at early stages of tumorigenesis. Unfortunately, these investigators did not use regular commercial cow milk, but they instead exposed their animals to milk protein powder re-suspended with water[619]. It is thus conceivable that the impact of milk EVs and MEX and their miR signaling was neglected by the selected feeding design. Retrospectively, they missed the complexity of milk signaling and thus provided a questionable conclusion.

Mendelian randomization studies

Larsson et al.[620] investigated the potential causal associations of milk consumption with the risk of PCa using genetic variants (rs4988235 or rs182549) near the LCT gene as proxies for milk consumption and reported no overall association between genetically predicted milk consumption and PCa (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.99-1.02, P = 0.389). However, there was moderate heterogeneity among estimates from different data sources (I2 = 54%). In contrast, a positive association was observed in the FinnGen consortium (OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 1.01-1.13, P = 0.026), which was more homogenous than the two other European populations [UK Biobank cohort and Prostate Cancer Association Group to Investigate Cancer Associated Alterations in the Genome (PRACTICAL) consortium]. Notably, per capita milk consumption in Finland (100.8 kg in 2020) is the highest in Europe[621]. The approximations of milk intake were based on data of rs4988235 (LCT-12910C>T) of a sub-cohort of 12,722 participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-InterAct study[622]. The median milk consumption was 162 g/day (25th-75th percentile, 37-300 g/day) and each additional milk intake increasing allele of rs4988235 was associated with an increase in milk consumption of 17.1 g/day (P = 2 × 10-7). Unfortunately, rs4988235 was not available in the FinnGen consortium, and instead a proxy SNP (rs182549) in complete linkage disequilibrium was used. A further limitation of Mendelian randomization studies is the fact that they do not present certain data on the real daily amount of consumed milk, milk’s thermal processing method used in the analyzed study cohorts, and the period of milk consumption during individual life periods as well as the potential impact of maternal milk consumption on fetal prostate development, a critical period for nutritional epigenetic programming of non-communicable diseases and non-hereditable genotypes[445,623-624].

Meta-analyses and umbrella reviews

Epidemiological studies are also afflicted with severe insufficiencies, as no study reported in the literature paid attention to the thermal processing of milk (pasteurization versus UHT), which significantly modifies the survival and biological activity of milk EVs and MEX and their miRs[421,424,426]. Meta-analyses of meta-analyses (so-called umbrella reviews[625]) mixing cohorts with low milk intake (Asian people) and cohorts with high milk intake (US citizens and Europeans) further modified by different types of thermal milk processing (predominant UHT processing in Southern European countries and preferential pasteurization in Northern European countries) are very questionable scientific approaches from the point of milk’s physiology. Furthermore, no study considered the complete spectrum of vulnerable periods of milk intake during lifetime exposure on prostate tumorigenesis (fetal period, childhood, puberty with final prostate gland differentiation, and adulthood) [Figure 3]. Nevertheless, it is astonishing that, despite these variances and insufficiencies, the majority of dairy industry-independent meta-analyses and prospective studies were able to relate milk consumption with an increased risk of PCa[10,12,13,14,168-175], whereas a recent review series sponsored by the Interprofessional Dairy Organization (INLAC) of Spain concluded that milk and dairy product consumption is not associated with increased all-cause mortality[626] and is not associated with an increased risk of PCa[627].

CONCLUSION

As shown in this review, milk consumption provides a symphony of signals activating PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 and synergistically operates on overactivated PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling pathways of PCa[21,154]. There is no monocausal agent such as calcium, IGF-1, estrogens, BMMFs, or other single compounds that exclusively promote cancer cell growth and PCa development. However, the molecular crosstalk of IGF-1, androgens, estrogens, and milk-derived miRs functionally converge with well-characterized genetic and epigenetic deviations of PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signal transduction in PCa[22,23,63-68].

Practices of veterinary medicine and dairy research to increase milk yield via holding dairy cows in permanent pregnancy (increase in milk estrogens)[373-377] and selection for high-yield dairy cows (increase of milk miR-148a)[469,470] combined with the induction of pasteurization and refrigeration technology changed the magnitude and biological character of milk-derived signals compared to ancient times, when the total amount and type of dairy intake were predominantly fermented milk products (cheese, yogurt, and kefir)[426].

Pasteurization of milk was introduced as an unproven technology without prior scientific information of its long-term effects on human health. Pasteurization combined with refrigeration allowed the large-scale introduction of milk’s epigenetic signaling machinery into the human food chain, recently promoted as a nutritional and therapeutic opportunity[628]. In contrast to UHT processing of milk, milk EV-derived miRs survive pasteurization, as recently confirmed[629]. We are very concerned that food augmentation with oncogenic MEX-derived miRs will further promote milk-related cancers such as PCa and breast cancer[450]. From the medical point of view, we claim to remove milk’s EVs and MEX from the human food chain to avoid their oncogenic effects[450].

Cow milk consumption in Western societies is a lifelong exposure beginning during fetal life. The fact that maternal milk consumption promotes fetal growth[580-583] implies early effects on prostate development and morphogenesis. In contrast to fermented milk (cheese), only maternal milk intake is correlated with BW[580-583] and increased risk of PCa[10]. It is thus of critical concern that webpages of medical societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists[630] and John Hopkins Medicine[631] still promote milk intake during pregnancy and do not differentiate between the biological effects of milk and those of fermented milk products on fetal development. The next vulnerable window for milk-mediated disturbances is puberty, the period of final morphogenesis of the prostate. Milk-mediated over-stimulation of the sebaceous gland (acne vulgaris), skeletal growth (linear overgrowth), and invisible and undetected changes of the prostatic gland (the potential seeding period of PCa) occur apparently simultaneously during puberty when young men consume milk, especially when fortified with whey protein concentrates combined with androgen abuse to increase muscle mass and physical appearance[632]. In concert with obstetricians and gynecologists, pediatricians recommend milk intake for children and federal governments support school milk consumption[633]. According to Agostoni et al.[634], a maximum daily intake of 500 mL cow milk should be provided to children above the age of 12 months. Although these authors appreciated milk-induced increases of IGF-1 and linear growth, they neglected associations with noncommunicable diseases[634]. Puberty with the final differentiation of the prostatic gland appears to be a very vulnerable life period for milk’s impact on PCa pathogenesis, a critical issue that is only addressed in two epidemiological studies[10,168] but no clinical study.

For adult men, further continuous milk consumption is recommended by orthopedics as a valuable source of calcium for the putative prevention of bone loss[161,635,636]. Thus, important disciplines of Western medicine promote milk consumption during lifetime with very restricted views to the demands of their own specialty. There is no epidemiological study that provides data for milk intake over all vulnerable periods of life. There is no epidemiological study paying attention to the thermal processing of milk, which affects the bioavailability of milk EVs. Very recent evidence in rodent models demonstrates that bovine milk EVs promote cancer metastasis[637]. Further studies of the protooncogene MDM4 as a central node of bovine MEX interconnectivity may be promising for a deeper understanding of milk’s impact on PCa pathogenesis. We hope that our review stimulates urologic oncology to address these questions in future research to prevent epidemic PCa.

DECLARATIONS

AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank Claus Leitzmann, University of Giessen, Germany and Harald zur Hausen, German Cancer Reseach Center (DKFZ) for constructive discussions of milk’s impact on human health.

Authors’ contributionsConception and design: Melnik BC

Administrative and scientific support: John SM, Weiskirchen R, Schmitz G

Collection and assembly of data: Melnik BC, Schmitz G

Data analysis and interpretation: Melnik BC, Schmitz G, Weiskirchen R, John SM

Manuscript writing: Melnik BC

Final approval of the manuscript: Melnik BC, John SM, Weiskirchen R, Schmitz G

Availability of data and materialsData in this review were derived from searches of the PubMed database.

Financial support and sponsorshipNone.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/27-Prostate-fact-sheet.pdf [Last accessed on 17 Dec 2021].

2. Culp MB, Soerjomataram I, Efstathiou JA, Bray F, Jemal A. Recent global patterns in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol 2020;77:38-52.

3. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-49.